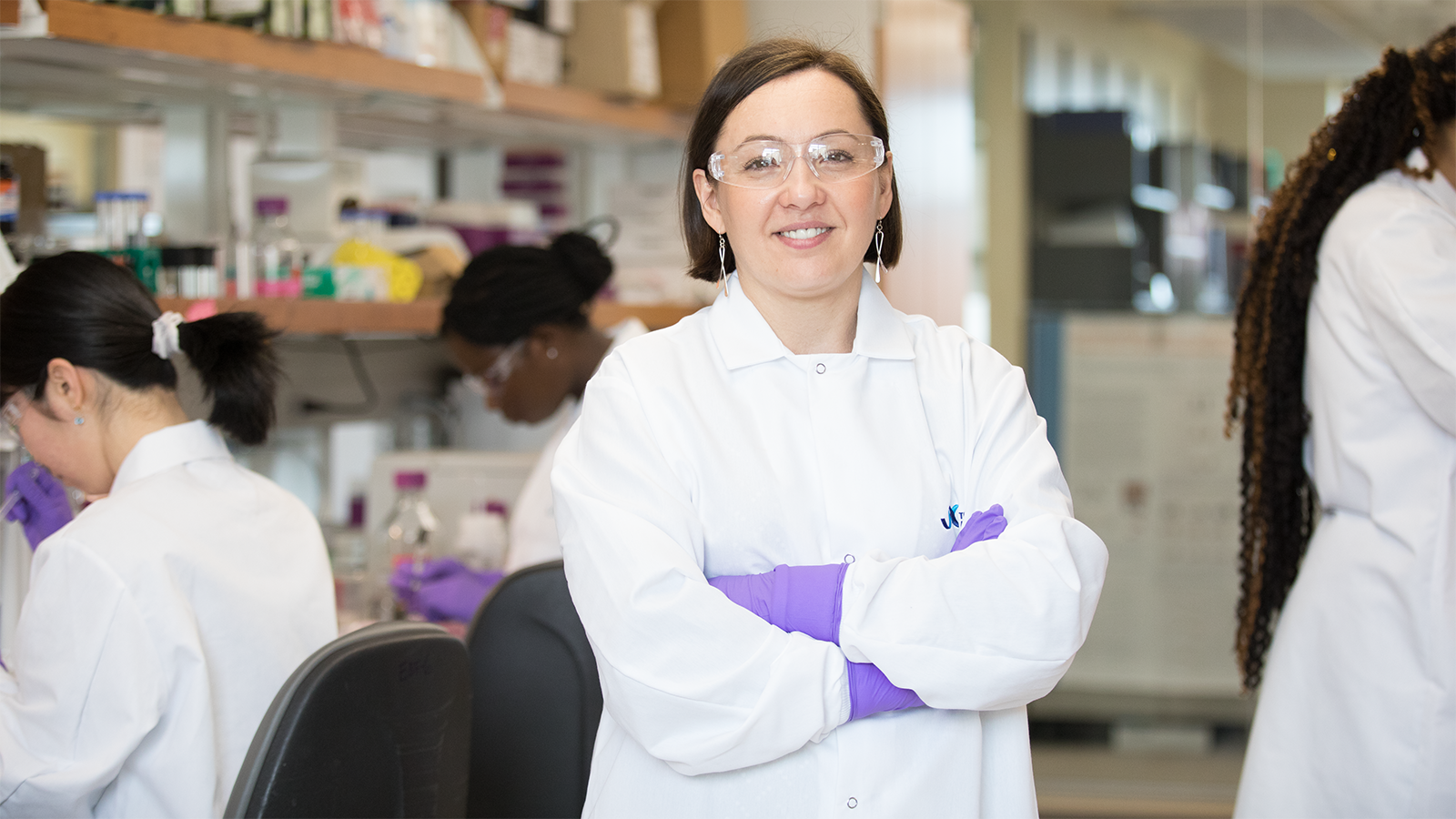

Ewelina Bolcun-Filas, Ph.D., is surrounded by inspiration. Her lab works out of a sunny space on the second floor of The Jackson Laboratory's sprawling Bar Harbor headquarters. Glimpses of evergreen mountains are visible beyond the desks where graduate students sort through microscope-captured images of mouse ovaries.

Ewelina Bolcun-Filas, Ph.D.Researching meiosis, the mechanisms of DNA damage detection and repair during normal development of gametes, and implications for fertility of cancer patients after radiation and chemotherapy.Bolcun-Filas 's lab studies fertility, and they inherited this space from a previous generation of JAX reproductive biologists. Bolcun-Filas's last lab was in a newer building, but she prefers this one: "There's a lot of history here."

Hanging above her team's computer monitors is a framed copy of Molecular Cell from April 1998, when Bolcun-Filas herself was an undergraduate genetics major in Poland. The cover is a psychedelic photograph of meiotic chromosomes taken by the JAX scientists who did their work on the same benches years ago. For Bolcun-Filas, this 23-year-old journal cover is more inspiring than any motivational poster. “That will be us one day," she laughs.

Bolcun-Filas studies the genetics of fertility and ways to protect fertility in cancer patients. She’s especially interested in the molecular pathways that control the development of healthy oocytes, the cells in the ovaries that go on to become eggs. Understanding how these pathways can be manipulated could hold the key to preserving ovarian function in cancer patients.

Studying oocyte development—which takes place before an individual is even born—is technically and scientifically challenging. It also requires navigating the social stigma around female infertility and reproductive health. Today, Bolcun-Filas is part of a vocal new generation of reproductive biologists, many of them women, who are bringing their talent and experiences to the field of fertility.

Preserving Fertility During Cancer Treatment

Bolcun-Filas discovered her passion for genetics in her final year of high school. She went on to specialize in reproductive biology during grad school.

"The coolest genetics happens during a production of sperm and egg," Bolcun-Filas said. “That's when genes reshuffle. The basis of genetics will always be linked to fertility.”

At first, she studied male fertility. It’s much simpler to investigate the development of sperm cells than eggs because sperm are constantly produced in males during their reproductive years. On the other hand, oocytes develop in the ovaries during gestation, so capturing the different stages of oocyte development requires looking at embryos of different ages. Bolcun-Filas came to JAX partly because the lab offered her the resources necessary to perform these difficult research procedures in mice.

Bolcun-Filas became interested in the issue of fertility in cancer patients while studying the process of recombination during which the genes from mom and dad are reshuffled in oocyte to produce eggs with unique genetic blueprints. Think of each gene like a LEGO brick. During recombination, the piece can be taken apart and put back together in new combinations.

Sometimes, though, an oocyte can’t properly reconnect the LEGO bricks on time. During a quality control checkpoint, these oocytes are flagged as duds and killed off through a process called apoptosis. Bolcun-Filas identified the protein that is responsible for flagging these “at risk” oocytes. By turning off this protein in mice, she and her team could save these oocytes from apoptosis and give them more time to reconnect the LEGO bricks.

Bolcun-Filas soon recognized that this discovery could be used to help cancer patients. Radiation exposure can break up oocyte DNA in a similar way to recombination. Theoretically, oocytes would put the LEGO-like gene pieces back together after radiation just like they do during recombination. However, the same checkpoint protein that is active during recombination targets these damaged cells before they get the chance to repair themselves. Because females are born with all the oocytes they will ever have, the death of these irreplaceable cells can lead to infertility and premature menopause.

When Bolcun-Filas turned off the checkpoint protein in mice, their oocytes were spared, and the mice gave birth to healthy offspring. It is challenging to confirm whether the oocytes could completely repair their DNA but healthy mouse pups suggest that they do. However, preserving even unusable oocytes has advantages.

If a young woman undergoing cancer treatment loses all her potential eggs, she can enter premature menopause. “The eggs in the ovaries are like batteries,” Bolcun-Filas explained.

When an egg matures, it triggers a release of hormones from the ovaries. Without developing eggs, ovary will stop producing female hormones, and the patient will enter menopause. This can make it difficult for the cancer survivor to have children even with implanted frozen embryos—the standard practice for preserving fertility before a patient begins radiation or chemotherapy.

"We hope that the eggs that we do save are good, but we can also help women to have kids from frozen eggs by ensuring that their ovaries work properly and produce hormones needed for women’s overall health," Bolcun-Filas said.

Paying it Forward

Bolcun-Filas is excited by the promise of her research. “For a long time, this sort of applicability of my research was far away,” she said. “We want to do research on how life works out of curiosity, but also to improve lives.”

Bolcun-Filas is also addressing the insensitivity and stigma that can accompany fertility concerns in medicine. As outcomes for cancer patients improve, a focus on survivors’ post-treatment quality-of-life is more important than ever.

Making fertility a specific priority in treatment plans for young cancer patients requires overcoming deeply embedded stigmas around reproductive health; some doctors are still uncomfortable discussing fertility or don’t consider it as an important issue. Bolcun-Filas noted that this is slowly changing due to the efforts of the Oncofertility Consortium, an international initiative focused on the intersection of cancer and fertility. Cancer doctors are now more likely to refer patients to fertility specialists who can help them make informed choices during their treatment.

“That education, that chance to talk about it is very important," Bolcun-Filas said.

She hopes her research will also contribute to the change. "I think science is often a question of if you have loud voices who advocate for an issue it will become a priority,” Bolcun-Filas said. “The Jackson Laboratory is a great amplifier of our voices. JAX organizes events such as 'Women X Women' where we can share our research on women’s health with the public.”

She is also championing opportunities for women to become leaders in science and bring more urgency to women’s health research.

"I think it's not necessarily that only women work on these problems or should work on these problems. But I think because we have a more personal relationship with the research, it's easier to talk about this,” she said. “And the more we hear about an issue, the easier it will be to fund.”

Rose Besen-McNally, a graduate student in the Bolcun-Filas Lab, agrees that scientists shouldn’t have to leave their lived experiences at the door when they enter the lab. She became interested in women’s health after her family members went through treatment for breast and ovarian cancer.

"These are issues that I am passionate about and have a personal connection to," she said. "I think that being a woman and researching these topics as someone who could potentially experience them gives you a unique ability to think about what the issue is like in reality, not just in the lab."

Besen-McNally says she is grateful for Bolcun-Filas and all the women who have mentored her.

"It's encouraging to work for someone who has been through the same path you're going down," she shared. “It's a different experience being a woman in science. It is nice to have someone who could listen to what I was saying and understand.”

In her history-filled lab space, Bolcun-Filas still uses lab glassware labeled with the names “Handel” and “Eppig”— two former faculty members who she considers mentors. Grateful for the guidance she received as a junior researcher, Bolcun-Filas is paying it forward by empowering scientists-in-training like Besen-McNally. As young biologists drive new advancements in reproductive health, these networks of mentorship are not just good for women in science—they’re good for women everywhere.