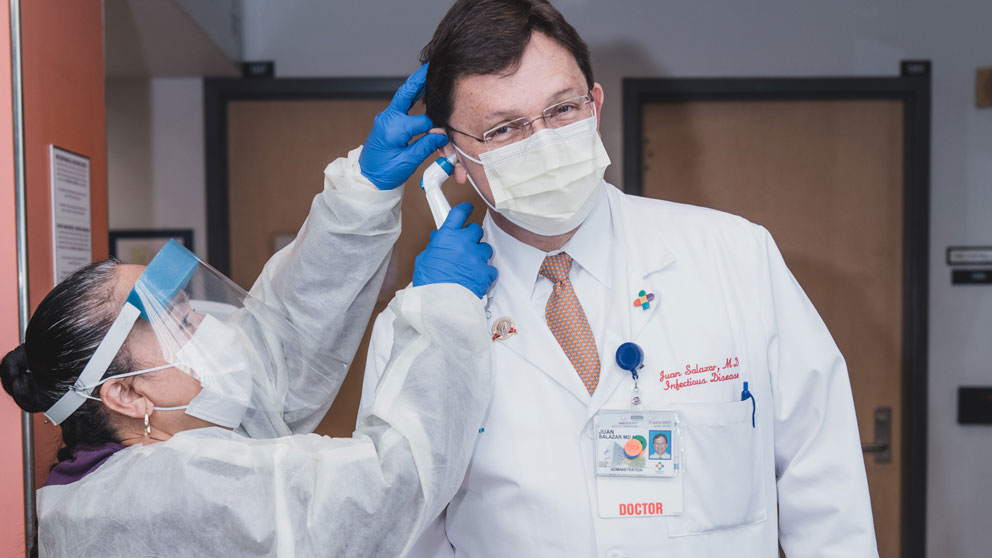

A nurse takes the temperature of Dr. Juan Salazar at Connecticut Children's. Photo courtesy Erin Blinn-Curran.

Connecticut Children’s is partnering with The Jackson Laboratory for virus testing and research into a post-viral immune syndrome.

It’s a bright spot in the gloom of the COVID-19 crisis: The effects of the SARS-CoV-2 virus are generally less severe in children than in adults, and most kids recover quickly and fully. This is in contrast with influenza and most other respiratory viruses, for which adults and children share similar levels of severity and mortality.

At Connecticut Children’s in Hartford, for example, all 16 children who tested positive for COVID-19—including a two-month-old infant—have survived. “It's a much milder disease, even in the critical care setting, than what has been seen in adults,” says Juan C. Salazar, M.D., M.P.H., F.A.A.P., the pediatric infectious disease expert who is Connecticut Children’s physician-in chief. “And that’s good news.”

But Salazar and other pediatricians are observing the emergence of a worrying multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C) among children who have had COVID-19. Symptoms of MIS-C, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, range from fever, vomiting and rash to breathing trouble, severe pain in the chest or abdomen, and inability to wake up or stay awake.

“We have six confirmed cases based on antibody testing,” Salazar says, “and there are a few others under investigation. Yale New Haven Children’s Hospital has another dozen or so. So probably for the state of Connecticut, there are around 20 kids who at least partially meet the definition of the syndrome. And we'll be seeing more.” He notes that because the the majority of kids now test negative for the SARS-CoV-2 virus, “that suggests that this is a post-infectious syndrome as opposed to an acute infection.”

These kids with MIS-C get “really sick,” Salazar says. “They present symptoms like septic shock: collapse of their blood pressure, myocarditis with cardiac enzymes that go up. They also develop disseminated intravascular coagulation, and it's really an acute small blood vessel vasculitis with severe compromise.”

But unlike toxic shock patients, “once you treat the MIS-C patients, once you turn the inflammatory process off, they get better. And we've seen kids that were in critical care, and then they walk out of the hospital and go home. It's really remarkable. This is another one of these odd things about this virus.”

MIS-C has also been compared to Kawasaki disease, an illness usually seen in patients between six months and six years of age, which causes inflammation in blood vessels throughout the body. “In a typical year we see about a dozen kids with Kawasaki. They look ill but they’re not critically ill, like the MIS-C patients. We treat them with intravenous gamma globulin and sometimes steroids, and after a few days in regular in-patient care they go home.”

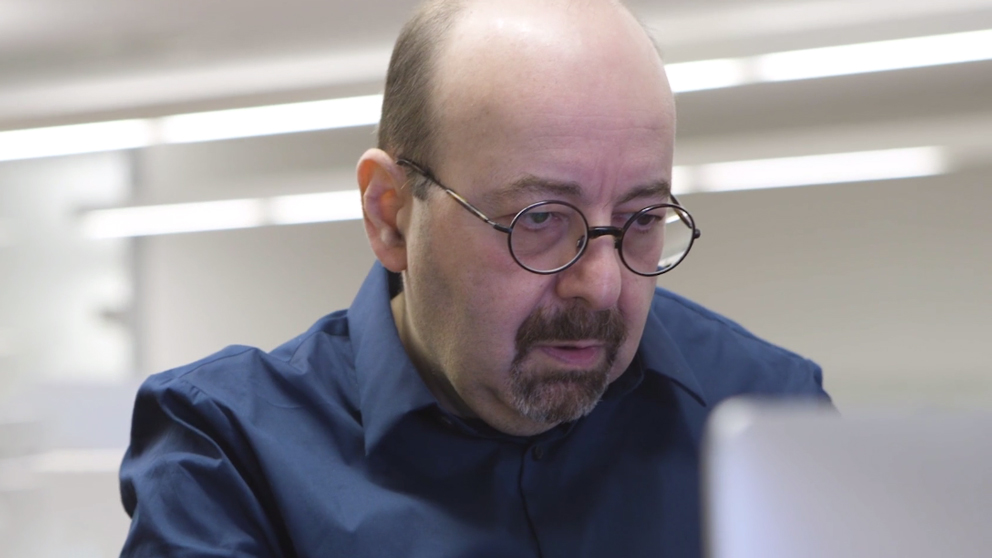

Derya Unutmaz, M.D. JAX photo by Tiffany Laufer.

Investigating MIS-C

Derya Unutmaz, M.D., is an immunology researcher and professor at The Jackson Laboratory (JAX) for Genomic Medicine in nearby Farmington, Conn. “Why is this post-viral issue occurring?” Unutmaz asks. “Does it involve a too-strong immune system, which is great at getting rid of the virus but may be triggering this later effect? These are pure speculations right now, but that’s a possibility.”

When Salazar started noticing the patients at Connecticut Children’s exhibiting the signs of MIS-C, Unutmaz says, “even though there were just a few of them, he immediately contacted me and said, ‘We’ve got to do something about this, and you’ve got the expertise to look at their blood.’”

Though MIS-C syndrome is still fortunately quite rare, Unutmaz says, “we anticipate that there will be more cases in the future, as more children recover from COVID-19.” Using blood samples from Connecticut Children’s patients, his lab will be analyzing the components of their immune systems, determining whether there are signs of hyperactivity or inaccurate regulation.

“You can think of the immune system as a well-prepared army,” Unutmaz explains, “with guns loaded and ready to attack. But this is not always good news, because it can be very dangerous if the weapons are not fired in the right direction.”

Unutmaz and Salazar are exploring to what extent the children have developed immunity to the COVID-19 virus, by measuring antibodies in their blood. “In particular, we're looking at neutralization by these antibodies, whether there's some sort of a correlation,” Unutmaz says. “Clearly, these kids had the virus. And even if they now test negative for it and have apparently eliminated most of the virus, it could be persisting somewhere in their body.”

They are also looking into the cellular immunity that the MIS-C patients have developed to the virus. “The immune system has both smart missiles that bind to the virus, blocking its entry into the cell, and other components that act like special forces: They hunt down cells infected with the virus and kill them so that those cells don’t replicate the virus and spread it to neighboring cells. We're trying to find both of those immune components to see if there's some sort of a correlation between this disease and the response to the virus itself.”

Unutmaz describes Salazar, whom he met soon after arriving at JAX in 2015, as “a fantastic clinician and a great scientist.” Before the COVID-19 pandemic the two immunology experts had been collaborating on studies of MECFS, or chronic fatigue syndrome, and more recently of Lyme disease. “In both diseases,” Unutmaz says, “there appears to be some kind of infection that triggers an immune response, and even after the infection is gone, the immune system keeps working as if there was still a threat.”

A career dedicated to children

Salazar says he chose pediatrics because “I think children are the future, I'm very comfortable around them, and they make my life happier. I'm a child at heart, always have been and always will be.”

His focus on infectious diseases and immunology began when he was a pediatric resident at the University of Connecticut in the late 1980s. “This was during a prior pandemic that is still active, which is HIV. I worked in the inner city of Hartford, an epicenter of the HIV pandemic. We used to see two or three kids a month that would be diagnosed with HIV, and many of them died because we had no therapies then.”

One of Salazar’s first patients was Jessica, a toddler who was diagnosed with perinatal-acquired HIV. “I took over her care when I was an intern,” he recounts. “And she was my patient all the way through my chief resident year, until she died from complications from HIV at the age of four. And that's when I knew I wanted to focus on infectious diseases, to give kids like Jessica a better chance at life.”

Salazar has been at UConn Health and Connecticut Children’s since 1998, where he is now Chair of the Department of Pediatrics, executive vice president of academic affairs and director of the pediatric and youth HIV program, as well as physician-in-chief. At UConn School of Medicine he conducts research in spirochetal diseases, including Lyme disease and syphilis. Besides Unutmaz at JAX, Salazar collaborates with translational and clinical researchers in Southern China, Malawi and Cali, Colombia. In collaboration with Justin Radolf at UConn Health and Anthony Moody at the Duke Vaccine Center, he is working in the development of a syphilis vaccine.

COVID-19 and children

When a child with symptoms of COVID-19 comes to Connecticut Children’s, he or she goes to a special section of the emergency department that is designated as a special infection unit. Once admitted, the child either goes to the critical care unit with its own COVID-19 section or a special isolation unit in the inpatient area.

“Obviously,” Salazar says, “every member of the hospital team involved in every step of the receiving process must be in full personal protective equipment, because we don't know which of those patients actually have COVID-19. So far we’ve tested more than 200 kids, and fortunately most of them test negative.”

As the pandemic has progressed, he notes, “we’re seeing more kids now than at the beginning. We suspect this has to do with some of the first wave of adult COVID-19 patients that are now going back to their home settings, and there’s probably some secondary transmission to children.”

Of the patients who tested positive for the virus, Connecticut Children’s team has observed more severe symptoms in those in their mid to late teens. And, as has been observed at other hospitals, morbid obesity and type two diabetes are severe risk factors for developing COVID-19.

Salazar says, “The pandemic has affected us very directly, in the sense that we've set up our systems, our hospital, our testing, everything, in preparedness for the kids that are coming in. We have done, I think, a very good job of making sure that the staff remains safe and that the patient gets taken care of.”

Accurate and rapid COVID-19 testing is vital to every aspect of Connecticut Children’s, he says. “If a kid comes to the operating room, that’s the only way we can know for sure that the kid isn’t shedding virus, and exposing the anesthesiologist, the surgeons or the surgical nurses to the virus.”

Children with cerebral palsy or other disabilities have not been able to come to the hospital for their speech or physical therapy, he says, “and that really delays them tremendously. They’re suffering right now. I want them to get back to their therapy but make sure that we’re not exposing the therapists to an undiagnosed SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

At Connecticut Children’s, all testing is outsourced to outside organizations, including Hartford HealthCare for inpatient tests. When Salazar learned that JAX was developing COVID-19 testing in their CLIA lab, he contacted JAX Genomic Medicine scientific director Charles Lee, Ph.D., FACMG.

“I see the partnership with JAX and the increased capacity to do CLIA testing as the solution for Connecticut Children's,” Salazar says. “I trust that this is exactly the kind of tests that would be perfectly done by JAX. And if we can up the scale of production of this, we can make it safe for kids to come to us for the care they need, and we can protect our doctors, nurses, therapists, assistants and everyone else on our staff.”