An evolutionary perspective on senescence

Cellular senescence, that is the loss of proliferative capacity, has a complex role in homeostasis. On the one hand, senescence is thought to protect tissues from potentially oncogenic stimuli such as DNA damage. On the other hand, senescence is hypothesized to underlie the cellular dysfunction that is associated with aging. Senescent cells in aging tissues are characterized by increased inflammatory cytokine and growth factor secretion. Interestingly, similar secretory responses occur during tissue injury. In a study published the December 2014 issue of Developmental Cell, a team led by Dr. Judith Campisi of the Buck Institute for Research on Aging and of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, investigated this potential third role for senescence in wound healing (Demaria et al. 2014).

A 3-component transgenic mouse model to track and manipulate senescent cells in vivo.

In their study, the Campisi team developed a transgenic mouse model to label and eliminate cells undergoing cellular senescence. In this model, the senescence-sensitive promoter from the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (Cdkn2a) gene, also known as p16INK4a, drives expression of 3MR, a fusion protein that is composed of luciferase and red fluorescent protein (RFP) reporters and herpes simplex virus-1 thymidine kinase, which converts ganciclovir (GCV) into an apoptosis inducer. Using these p16-3MR mice and in vivo bioluminescent imaging, the researchers observed a robust, but transient, increase in senescent cells at the site of cutaneous injury. The presence of these labeled cells coincided with wound-healing markers, such as p16, p21, SA-β-gal, and inflammatory and pro-angiogenic molecules.

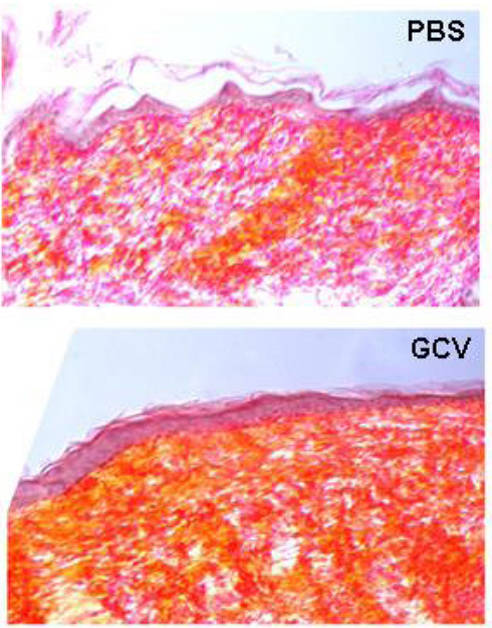

When senescent cells were killed by GCV treatment, wound closure was delayed, and immune and endothelial cells were absent. Although their wounds eventually healed, GCV treated mice had substantial fibrotic tissue at the injury site. Likewise, p16/p21 double knockout mice, which have very few senescent cells, showed similar delays in wound closure. Together, these results suggest that senescent cells accelerate and improve tissue repair.

Senescent cells supply beneficial growth factors which promote myofibroblast differentiation.

Figure 1. Scar tissue (stained for collagen, in orange) is evident in healed wounds from transgenic p16-3MR mice lacking senescent cells (bottom panel, GCV-treated) compared to control mice (top panel, PBS-treated).

To understand how senescent cells promote repair, the Campisi team surveyed wound sites in GCV-treated p16-3MR mice and found fewer endothelial cells and fibroblasts, including myofibroblasts, which are contractile cells responsible for wound closure. In addition, they discovered that senescent cells fluorescently isolated from p16-3MR wounds produced large amounts of PDGF-AA, a mitogen and chemoattractant for fibroblasts. Interestingly, PDGF-AA applied topically to GCV-treated mice increased myofibroblast numbers and rescued wound closure rates. Based on these findings, the Campisi team proposes that PDGF-AA derived from senescent cells stimulates local myofibroblast differentiation, allowing for greater contractility and more efficient wound closure.

Results from this study define an unanticipated role for senescence in tissue repair and suggest that topical application of PDGF-AA may accelerate and improve cutaneous wound healing. This research could have practical implications clinically for reducing post-operative infections and for treating cutaneous wounds associated with diabetes.

Additional Research Resources Available:

The p16-3MR mouse model was created and backcrossed to C57BL/6J (000664) using a “speed congenic” approach. If you have a mutation that you would like to transfer to a different genetic background, JAX offers both a comprehensive Speed Congenic Service as well as a Genome Scanning Service to assist you with backcrossing your mice at your facility.

Double p16 (Cdkn1a)/p21(Cdkn2a) knockout mice could be generated using some of these JAX strains: